Apparently, I have Impostor Syndrome. An estimated 70% of us do.

Even so, I don’t feel I should write this post. Who am I to write about my own experience?

I don’t even know how to spell it. Is it Imposter Syndrome? Or is it Impostor Syndrome?

That’s the essence of Imposter Syndrome. I always feel someone else knows more than me, even about my own life experience.

I’ll research to the point of ridiculousness. I feel like a giant fraud, at all times.

But my Impostor Syndrome? It’s totally reasonable.

I know millions of other people must be more talented and knowledgeable than me. That’s basic math.

My accomplishments? I got lucky.

I was born into a family that loved and supported me. I was born into a social system that gave me advantages. That’s basic Sociology.

If you try to sooth me by saying, “But you work hard!” — I will reply, “Hard work is irrelevant. Zillions of people work harder than I do. They weren’t as lucky as me.”

I know this. I will not be soothed. I will not be convinced of my worthiness.

Also, I’d rather not be labeled with any kind of syndrome. But if I had a choice between Impostor Syndrome and Expert Syndrome, I’d pick Impostor Syndrome. Some cool and accomplished people have Impostor Syndrome.

Tom Hanks? Maya Angelou? Sonia Sotomayor?

Shoot. I’m in good company.

So why is it that I’m frequently targeted with a blizzard of self-help articles on how to overcome Imposter Syndrome? My Impostor Syndrome has some positive outcomes. It fuels my self-deprecating humor. It inspires me to appreciate and respect the contributions of others. It motivates me to keep learning more.

In contrast, what about all those know-nothings who seem high on self-importance? Why aren’t they being hammered with articles to help them overcome their Expert Syndrome?

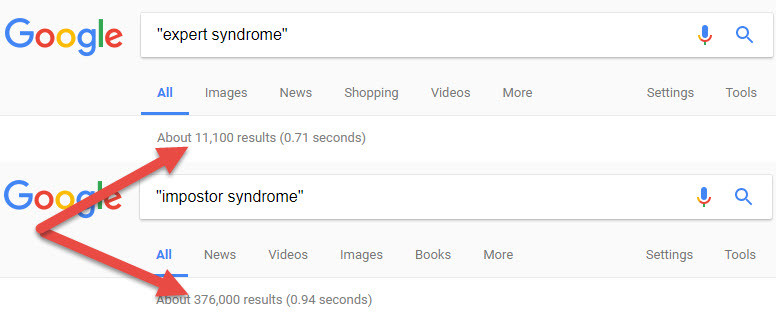

Check out these search results: that’s some kind of disparity in self-help volume.

It turns out, Expert Syndrome isn’t even real. It seems I made the term up in a fit of pique. Expert Syndrome doesn’t even have a Wikipedia entry. Instead, it’s called the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

That’s not phrase parity. I’m gonna continue to call it Expert Syndrome, by cracky.

Because no offense to Dunning or Kruger, but people instantly know what I mean when I say Expert Syndrome. You see it everywhere.

If someone with Expert Syndrome browses an article about a topic, they feel they’ve earned a Ph.D. on the subject. If they do an hour’s worth of mediocre work, they update their resume with their accomplishments — then alert the media. They might be tone-deaf, but they believe they can win American Idol.

Buoyed by overconfidence and entitlement, people with Expert Syndrome actually think they understand topics deeply or do things well. They feel they possess an incredible wealth of experience, talent, and knowledge.

But they don’t. They’re delusional.

It sounds hard to believe, but someone can demonstrate a long track record of failure – and still project confidence. And often, the public will overlook their obvious lack of knowledge, talent, and experience. Instead, they’ll fall for the swagger.

Expert Syndrome is a huge problem for organizations. People with Expert Syndrome interview well. They write impressive résumés. They display the charm that wins over recruiters, interviewers, and hiring managers. When they fail at work, they get promoted: because in our culture, outsized confidence often trumps lackluster results.

It’s not only a personal failing, it’s a cultural one. Organizations that value braggadocio are top heavy with people who lack knowledge, ability, empathy, and understanding.

And that’s one reason why there are few self-help articles directed at solving Expert Syndrome. There’s no target audience. A person with Expert Syndrome won’t recognize themselves — so they won’t even feel tempted to read it.

Society provides no incentive for those with Expert Syndrome to seek help. Instead, they are often rewarded for their behavior.

That brings us back to Impostor Syndrome. The 70% of us who have it? We might be the only hope to end the scourge of Expert Syndrome.

We need to take an ironic first step: we need to pretend we have confidence. When it comes to displaying confidence, we actually need to become the impostors we think we are.

I know you won’t do this for you. You’re probably not much of a “personal gain” kind of person.

But maybe you’ll fake confidence to help others. We need talented and thoughtful people. We need people with empathy and insight. We need to work with people who are actually aware of the simple fact they don’t know everything.

That’s why you need to at least pretend to be confident. If you don’t, we might have to continue to work with insufferable blowhard know-nothings.

So don’t be selfish about this. Embrace your Impostor Syndrome — and learn to fake confidence.

Laura Bergells is a writer, teacher, and a #LinkedInLearning author. Check out her courses on Crisis Communication and Public Speaking.